Clayton Sampy

Clayton Sampy is another in a long line of Zydeco masters found in the Acadiana area of southern Louisiana. He was born in Carencro, just outside of Lafayette, in January 1949 and still lives there today. Sampy was one of eight siblings, and the whole family farmed, picking cotton, digging sweet potatoes, breaking corn and cutting okra. Life was hard, but relief came with weekend house dances where Zydeco music entranced young Clayton. His father Eugene Sampy Sr. played accordion at the parties and Clayton's older brother Eugene Jr. was beginning on accordion and guitar.

Later, Eugene Sampy Jr. became the leader of a well-known local Zydeco band called Sampy and the Bad Habits. Eugene taught Clayton how to play bass, and by age 17, Clayton was a member of the Bad Habit Band. The experience opened his eyes to how popular Zydeco had become, and he began to appreciate his French-speaking Creole culture as special.

It was a Saturday evening in 1980 at the Blue Angel club in Lafayette when Sampy decided for good that he would make Zydeco music the centerpiece of his life. The parking lot of the club was full and cars had parked on side streets for a mile around. Sampy had never seen anything like it. He asked the doorman who was playing. It was Clifton Chenier, and Sampy had found himself a hero. Chenier was wearing a beautiful, ornate crown, signifying his status as the King of Zydeco, and his look and sound completely floored Sampy. He decided on the spot to drop his bass guitar in favor of the accordion. He wanted to be everything that he saw in Clifton Chenier that night.

Sampy bought an accordion and before long formed his own band, Clayton Sampy and the Zydeco Farmers. They toured Louisiana and east Texas and shared stages with all of the Zydeco greats, most importantly, Clifton Chenier. Sampy became close friends with Chenier, and towards the end of Chenier's life, when his failing health limited his abilities on stage, the King of Zydeco invited Sampy to help him on his gigs. Sometimes Chenier was physically unable to make the gig, and Sampy became his chosen fill-in. It was an honor that Sampy holds dear to his heart, and he's since dedicated his career to carrying on what Chenier started.

Clayton Sampy is another in a long line of Zydeco masters found in the Acadiana area of southern Louisiana. He was born in Carencro, just outside of Lafayette, in January 1949 and still lives there today. Sampy was one of eight siblings, and the whole family farmed, picking cotton, digging sweet potatoes, breaking corn and cutting okra. Life was hard, but relief came with weekend house dances where Zydeco music entranced young Clayton. His father Eugene Sampy Sr. played accordion at the parties and Clayton's older brother Eugene Jr. was beginning on accordion and guitar.

Later, Eugene Sampy Jr. became the leader of a well-known local Zydeco band called Sampy and the Bad Habits. Eugene taught Clayton how to play bass, and by age 17, Clayton was a member of the Bad Habit Band. The experience opened his eyes to how popular Zydeco had become, and he began to appreciate his French-speaking Creole culture as special.

It was a Saturday evening in 1980 at the Blue Angel club in Lafayette when Sampy decided for good that he would make Zydeco music the centerpiece of his life. The parking lot of the club was full and cars had parked on side streets for a mile around. Sampy had never seen anything like it. He asked the doorman who was playing. It was Clifton Chenier, and Sampy had found himself a hero. Chenier was wearing a beautiful, ornate crown, signifying his status as the King of Zydeco, and his look and sound completely floored Sampy. He decided on the spot to drop his bass guitar in favor of the accordion. He wanted to be everything that he saw in Clifton Chenier that night.

Sampy bought an accordion and before long formed his own band, Clayton Sampy and the Zydeco Farmers. They toured Louisiana and east Texas and shared stages with all of the Zydeco greats, most importantly, Clifton Chenier. Sampy became close friends with Chenier, and towards the end of Chenier's life, when his failing health limited his abilities on stage, the King of Zydeco invited Sampy to help him on his gigs. Sometimes Chenier was physically unable to make the gig, and Sampy became his chosen fill-in. It was an honor that Sampy holds dear to his heart, and he's since dedicated his career to carrying on what Chenier started.

Amédé Ardoin (March 11, 1898 – November 3, 1942) was an American Louisiana Creole musician, known for his high singing voice and virtuosity on the Creole/Cajun Accordion. He is credited by Louisiana music scholars with laying the groundwork for Cajun music in the early 20th century.

Ardoin, with fiddle player Dennis McGee, was one of the first artists to record the music of the Acadiana region of Louisiana. On December 9, 1929, he and McGee recorded six songs for Columbia Records in New Orleans.[2] In all, thirty-four recordings with Ardoin playing accordion are known to exist.

Life and career The date and place of his death is uncertain. Descendants of family members and musicians who knew Ardoin tell a story, now well-known, about a racially motivated attack on him in which he was severely beaten, probably between 1939 – 1940, while walking home after playing at a house dance near Eunice, Louisiana. The most common story says that some white men were angered when a white woman, daughter of the house, lent her handkerchief to Ardoin to wipe the sweat from his face.[3] Canray Fontenot and Wade Fruge, in PBS's American Patchwork, explained that after Ardoin left the place, he was run over by a Model A car and crushed his head and throat, damaging his vocal cords. He was found the next day, lying in a ditch. According to Canray, he "went plumb crazy" and "didn't know if he was hungry or not. Others had to feed him. He got weaker and weaker until he died." Others consider the story apocryphal. Other versions say that Ardoin was poisoned, not beaten, possibly by a jealous fellow musician.

Contemporaries said that Ardoin suffered from impaired mental and musical capacities later in his life, probably from that infamous night. He ended up in an asylum in Pineville, Louisiana, where he was admitted in September 1942. He died at the hospital two months later, and was buried in the hospital's common grave.[4]

Ardoin, with fiddle player Dennis McGee, was one of the first artists to record the music of the Acadiana region of Louisiana. On December 9, 1929, he and McGee recorded six songs for Columbia Records in New Orleans.[2] In all, thirty-four recordings with Ardoin playing accordion are known to exist.

Life and career The date and place of his death is uncertain. Descendants of family members and musicians who knew Ardoin tell a story, now well-known, about a racially motivated attack on him in which he was severely beaten, probably between 1939 – 1940, while walking home after playing at a house dance near Eunice, Louisiana. The most common story says that some white men were angered when a white woman, daughter of the house, lent her handkerchief to Ardoin to wipe the sweat from his face.[3] Canray Fontenot and Wade Fruge, in PBS's American Patchwork, explained that after Ardoin left the place, he was run over by a Model A car and crushed his head and throat, damaging his vocal cords. He was found the next day, lying in a ditch. According to Canray, he "went plumb crazy" and "didn't know if he was hungry or not. Others had to feed him. He got weaker and weaker until he died." Others consider the story apocryphal. Other versions say that Ardoin was poisoned, not beaten, possibly by a jealous fellow musician.

Contemporaries said that Ardoin suffered from impaired mental and musical capacities later in his life, probably from that infamous night. He ended up in an asylum in Pineville, Louisiana, where he was admitted in September 1942. He died at the hospital two months later, and was buried in the hospital's common grave.[4]

The undisputed "King of Zydeco," Clifton Chenier was the first Creole to be presented a Grammy award on national television. Blending the French and Cajun 2-steps and waltzes of southwest Louisiana with New Orleans R&B, Texas blues, and big-band jazz, Chenier created the modern, dance-inspiring, sounds of zydeco. A flamboyant personality, remembered for his gold tooth and the cape and crown that he wore during concerts, Chenier set the standard for all the zydeco players who have followed in his footsteps. In an interview from Ann Savoy's book, Cajun Music: Reflection of a People, Chenier explained, "Zydeco is rock and French mixed together, you know, like French music and rock with a beat to it. It's the same thing as rock and roll but it's different because I'm singing in French." The son of sharecropper and amateur accordion player, Joe Chenier, and the nephew of a guitarist, fiddler, and dance club owner, Maurice "Big" Chenier, Chenier found his earliest influences in the blues of Muddy Waters, Peetie Wheatstraw, and Lightnin' Hopkins, the New Orleans R&B of Fats Domino and Professor Longhair, the 1920s and '30s recordings by zydeco accordionist Amede Ardoin and the playing of childhood friends Claude Faulk and Jesse and Zozo Reynolds. Acquiring his first accordion from a neighbor, Isaie "Easy" Blasa in 1947, Chenier was taught the basics of the instruments by his father. By 1944, Chenier was performing, with his brother Cleveland on frottoir (rub-board) in the dance halls of Lake Charles.

Moving to New Iberia in the mid-'40s, Chenier worked in the sugar fields cutting sugar cane. After moving, to Port Arthur, TX, in 1947, he divided his time between driving a refinery truck and hauling pipe for Gulf and Texaco and playing with his brother. In 1954, Chenier signed with Elko Records. His first recording session, at Lake Charles radio station KAOK, yielded seven tunes including the regional hit single, "Cliston's Blues" and "Louisiana Stomp."

Chenier's first national attention came with his first single for the Specialty record label, "Ay Tete Fille (Hey, Little Girl)," a cover of a Professor Longhair tune, released in May 1955. The song was one of 12 that he recorded during two sessions produced by Bumps Blackwell, best known for his work with Little Richard. By 1956, Chenier had left his day job to devote his full-time attention to music, Touring with his band, the Zydeco Ramblers, which included blues guitarist Philip Walker. The following year, Chenier left Specialty and signed with the Chess label in Chicago. Although he toured, along with Etta James, throughout the United States, Chenier's career suffered when the popularity of ethnic and regional music styles began to decline. Although he recorded 13 songs for the Crowley, LA-based Zynn label, between 1958 and 1960, none charted.

The turning point in Chenier's career came when Lightnin' Hopkins' wife, who was a cousin, introduced Chris Strachwitz, owner of the roots music label, Arhoolie, to his early recordings. Strachwitz quickly signed Chenier to Arhoolie, producing his first single, "Ay Yi Yi"/"Why Did You Go Last Night?," in four years. Although they continued to work together until the early '70s, Chenier and Strachwitz differed artistically. While Chenier wanted to record commercial-minded R&B, Strachwitz encouraged him to focus on traditional zydeco. Chenier's first album for Arhoolie, Louisiana Blues and Zydeco, featured one side of blues and R&B and one side of French 2-steps and waltzes.

In 1976, Chenier recorded one of his best albums, Bogalusa Boogie, and formed a new group, the Red Hot Louisiana Band, featuring tenor saxophonist "Blind" John Hart and guitarist Paul Senegal.

Chenier reached the peak of his popularity in the '80s. In 1983, he received a Grammy award for his album, I'm Here!, recorded in eight hours in Bogalusa, LA. The following year, he performed at the White House. Although he suffered from kidney disease and a partially amputated foot and was required to undergo dialysis treatment every three days, Chenier continued to perform until one week before his death on December 12, 1987. Following his death, his son, C.J. Chenier, took over leadership of the Red Hot Louisiana Band.

Moving to New Iberia in the mid-'40s, Chenier worked in the sugar fields cutting sugar cane. After moving, to Port Arthur, TX, in 1947, he divided his time between driving a refinery truck and hauling pipe for Gulf and Texaco and playing with his brother. In 1954, Chenier signed with Elko Records. His first recording session, at Lake Charles radio station KAOK, yielded seven tunes including the regional hit single, "Cliston's Blues" and "Louisiana Stomp."

Chenier's first national attention came with his first single for the Specialty record label, "Ay Tete Fille (Hey, Little Girl)," a cover of a Professor Longhair tune, released in May 1955. The song was one of 12 that he recorded during two sessions produced by Bumps Blackwell, best known for his work with Little Richard. By 1956, Chenier had left his day job to devote his full-time attention to music, Touring with his band, the Zydeco Ramblers, which included blues guitarist Philip Walker. The following year, Chenier left Specialty and signed with the Chess label in Chicago. Although he toured, along with Etta James, throughout the United States, Chenier's career suffered when the popularity of ethnic and regional music styles began to decline. Although he recorded 13 songs for the Crowley, LA-based Zynn label, between 1958 and 1960, none charted.

The turning point in Chenier's career came when Lightnin' Hopkins' wife, who was a cousin, introduced Chris Strachwitz, owner of the roots music label, Arhoolie, to his early recordings. Strachwitz quickly signed Chenier to Arhoolie, producing his first single, "Ay Yi Yi"/"Why Did You Go Last Night?," in four years. Although they continued to work together until the early '70s, Chenier and Strachwitz differed artistically. While Chenier wanted to record commercial-minded R&B, Strachwitz encouraged him to focus on traditional zydeco. Chenier's first album for Arhoolie, Louisiana Blues and Zydeco, featured one side of blues and R&B and one side of French 2-steps and waltzes.

In 1976, Chenier recorded one of his best albums, Bogalusa Boogie, and formed a new group, the Red Hot Louisiana Band, featuring tenor saxophonist "Blind" John Hart and guitarist Paul Senegal.

Chenier reached the peak of his popularity in the '80s. In 1983, he received a Grammy award for his album, I'm Here!, recorded in eight hours in Bogalusa, LA. The following year, he performed at the White House. Although he suffered from kidney disease and a partially amputated foot and was required to undergo dialysis treatment every three days, Chenier continued to perform until one week before his death on December 12, 1987. Following his death, his son, C.J. Chenier, took over leadership of the Red Hot Louisiana Band.

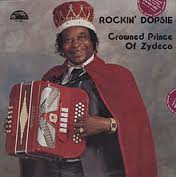

Rockin' Dopsie (a.k.a Rockin' Dupsee) (February 10, 1932 – August 26, 1993) was born Alton Rubin in Carencro, Louisiana. He was a leading Zydeco musician and button accordion player who enjoyed popular success first in Europe and later in the United States. If Clifton Chenier was the king of zydeco music, Rockin' Dopsie (pronounced doopsie; sometime) with his unequalled proficiency on the button accordion was its crown prince.[1]

Career Dopsie, who began performing professionally in the late 1940s, took his stage name from a Chicago dancer who had come to perform in Lafayette, Louisiana.[1]

Dopsie recorded his debut album with Sam Charters for Sweden's Sonet label. Over the next decade, Dopsie recorded five more albums for the label. Released in Europe, Dopsie soon became a popular performer. He began touring Europe twice annually in 1979. It was not until well into the 1980s that Dopsie's music began garnering attention back home. His U.S. career got a big boost in 1985 when he recorded "That Was Your Mother" with Paul Simon on the latter's Graceland album. Later, Dopsie would also record with other pop singers including Cyndi Lauper and Bob Dylan. He has also appeared in a few films, including Delta Heat.

Dopsie's first language was Louisiana Creole French, and he spread the Creole culture throughout the world by his music.

Since Dopsie's death from heart failure in 1993, his band, The Twisters, continues to perform; now led by his son Dopsie Jr., accordionist, vocalist and washboard player, with another son Alton Jr., on drums. He was also related to Chanda Rubin, who is a current tennis star. Dopsie's younger son, Dwayne, also plays accordion and leads his own band, Dwayne Dopsie & the Zydeco Hellraisers.

Career Dopsie, who began performing professionally in the late 1940s, took his stage name from a Chicago dancer who had come to perform in Lafayette, Louisiana.[1]

Dopsie recorded his debut album with Sam Charters for Sweden's Sonet label. Over the next decade, Dopsie recorded five more albums for the label. Released in Europe, Dopsie soon became a popular performer. He began touring Europe twice annually in 1979. It was not until well into the 1980s that Dopsie's music began garnering attention back home. His U.S. career got a big boost in 1985 when he recorded "That Was Your Mother" with Paul Simon on the latter's Graceland album. Later, Dopsie would also record with other pop singers including Cyndi Lauper and Bob Dylan. He has also appeared in a few films, including Delta Heat.

Dopsie's first language was Louisiana Creole French, and he spread the Creole culture throughout the world by his music.

Since Dopsie's death from heart failure in 1993, his band, The Twisters, continues to perform; now led by his son Dopsie Jr., accordionist, vocalist and washboard player, with another son Alton Jr., on drums. He was also related to Chanda Rubin, who is a current tennis star. Dopsie's younger son, Dwayne, also plays accordion and leads his own band, Dwayne Dopsie & the Zydeco Hellraisers.

Canray Fontenot (October 16[a],[1] 1922 - July 29, 1995[2]) was an American Creole fiddle player, who has been described as "the greatest black Louisiana French fiddler of our time."[3] Contents Early life Canray Fontenot was born in L'anse Aux Vaches, near Basile, Louisiana[3] (or l'Anse des Rougeaux, Louisiana, an unincorporated community outside Eunice, Louisiana); however his family was from Duralde, Louisiana.[4] Fontenot, who grew up working on a family farm, inherited his musical skills from his parents, who played accordion; his father Adam, known as "Nonc Adam", played with Amédé Ardoin.[3] Canray first played a cigar-box fiddle that had strings taken off the screen door of his home. His bow was made from the branches of pear trees and sewing thread.

Canray stated "So, we took some cigar boxes," he said. "In those days, cigar boxes were made of wood. So, we worked at it and finally made ourselves a fiddle. For our strings, we had no real strings ... we took strands off the screen door. We made fiddles out of that stuff, and then we started practicing." Fontenot visited a neighbor "to see how he tuned his fiddle. He would sound a string, and then I would try mine, but I couldn't go as high as his fiddle; every time I tried to match his pitch, I'd break a string.... But then when he would break a string, I would take the longest end. Then my fiddle sounded pretty good. And that's how I learned. It's just a matter of having music on your mind." [4] Music career By 1934, Fontenot had begun performing with Amédé Ardoin, who wanted him to play on a recording session with him in New York; however, his parents would not allow him to travel.[3] In the late 1930s, he formed a string band with George Lenard and Paul Frank, playing boogie woogie, western swing and jazz as well as traditional tunes, but after a few years Fontenot established a more lasting partnership with accordionist Alphonse "Bois Sec" Ardoin (a cousin of Amédé) from nearby Duralde. In 1948 the pair formed the Duralde Ramblers, who became highly popular in south west Louisiana and made many radio broadcasts through the 1950s, notably on KEUN in Eunice.[3] He also began writing songs. His most well-known original songs are "Joe Pitre a Deux Femmes," "Les Barres de la prison" and "Bonsoir Moreau", which have become standards in the Cajun music and Zydeco music repertoires.[2] Fontenot was never a professional musician; he was a rice farmer for many years, and also worked as a labourer in a feed store in the town of Welsh.[3]

Fontenot and Ardoin made their debut outside of Louisiana in 1966, performing at the Newport Folk Festival. At the time, Fontenot had not performed in public for several years, but was persuaded to do so by folklorist Ralph Rinzler.[3] Following the festival, the pair recorded an album with producer Dick Spottswood, Les Blues Du Bayou, and from then on started appearing in a steady stream of festivals in Louisiana and around the world, becoming the last Creole musicians playing music in the "old style".[3]

He was awarded the NEA National Heritage Fellowship in 1986, in the same year as he and Ardoin were appointed adjunct professors at the University of Southwestern Louisiana. In later years he was featured in many documentaries on Cajun and Creole culture, including the 1989 film "J'ai Ete au Bal" as well as PBS's American Patchwork "Don't Drop the Potato". He also performed in New Orleans and toured Europe with the band Filé.[3] There is a portrait of Canray in Yasha Aginsky's 1983 film "Cajun Visits," and in Jean-Pierre Bruneau's 1993 film "Louisiana Blues," edited by Yasha Aginsky.

Canray Fontenot died in 1995 after a long bout with cancer.

Canray stated "So, we took some cigar boxes," he said. "In those days, cigar boxes were made of wood. So, we worked at it and finally made ourselves a fiddle. For our strings, we had no real strings ... we took strands off the screen door. We made fiddles out of that stuff, and then we started practicing." Fontenot visited a neighbor "to see how he tuned his fiddle. He would sound a string, and then I would try mine, but I couldn't go as high as his fiddle; every time I tried to match his pitch, I'd break a string.... But then when he would break a string, I would take the longest end. Then my fiddle sounded pretty good. And that's how I learned. It's just a matter of having music on your mind." [4] Music career By 1934, Fontenot had begun performing with Amédé Ardoin, who wanted him to play on a recording session with him in New York; however, his parents would not allow him to travel.[3] In the late 1930s, he formed a string band with George Lenard and Paul Frank, playing boogie woogie, western swing and jazz as well as traditional tunes, but after a few years Fontenot established a more lasting partnership with accordionist Alphonse "Bois Sec" Ardoin (a cousin of Amédé) from nearby Duralde. In 1948 the pair formed the Duralde Ramblers, who became highly popular in south west Louisiana and made many radio broadcasts through the 1950s, notably on KEUN in Eunice.[3] He also began writing songs. His most well-known original songs are "Joe Pitre a Deux Femmes," "Les Barres de la prison" and "Bonsoir Moreau", which have become standards in the Cajun music and Zydeco music repertoires.[2] Fontenot was never a professional musician; he was a rice farmer for many years, and also worked as a labourer in a feed store in the town of Welsh.[3]

Fontenot and Ardoin made their debut outside of Louisiana in 1966, performing at the Newport Folk Festival. At the time, Fontenot had not performed in public for several years, but was persuaded to do so by folklorist Ralph Rinzler.[3] Following the festival, the pair recorded an album with producer Dick Spottswood, Les Blues Du Bayou, and from then on started appearing in a steady stream of festivals in Louisiana and around the world, becoming the last Creole musicians playing music in the "old style".[3]

He was awarded the NEA National Heritage Fellowship in 1986, in the same year as he and Ardoin were appointed adjunct professors at the University of Southwestern Louisiana. In later years he was featured in many documentaries on Cajun and Creole culture, including the 1989 film "J'ai Ete au Bal" as well as PBS's American Patchwork "Don't Drop the Potato". He also performed in New Orleans and toured Europe with the band Filé.[3] There is a portrait of Canray in Yasha Aginsky's 1983 film "Cajun Visits," and in Jean-Pierre Bruneau's 1993 film "Louisiana Blues," edited by Yasha Aginsky.

Canray Fontenot died in 1995 after a long bout with cancer.

John Delafose and his band the Eunice Playboys bridged the gap between zydeco's roots and its contemporary sound with a mastery matched by few of their peers; despite an affinity for early Creole styles, French lyrics and two-step waltz rhythms, they played with all of the fiery intensity demanded by modern-day audiences, tapping into a wide array of sources -- blues, Cajun, even country -- to forge a propulsive traditionalist sound all their own. Born April 16, 1939 in Duralde, Louisiana, Delafose as a child crafted fiddles and guitars out of old boards and cigar boxes fitted with window-screen wire; he eventually took up the harmonica, and at the age of 18 learned the button accordion. He soon turned to farming, and as a result did not seriously pursue music until during the early 1970s, at which time he served as an accordionist and harpist with a variety of local zydeco bands. By the middle of the decade his formed his own combo, the Eunice Playboys; originally featuring guitarist Charles Prudhomme and his bassist brother Slim, the group's lineup swelled over time to also include Delafose's sons John "T.T." on rubboard and Tony on drums. Another son, Geno, later joined as well, trading vocal and accordion leads with his father. Delafose and the Eunice Playboys debuted in 1980 with the regional hit "Joe Pete Got Two Women," from the LP Zydeco Man; Uncle Bud Zydeco followed in 1982, and as interest in traditional Creole culture swelled, the group became one of the hottest attractions on the Gulf Coast circuit. They returned in 1984 with Heartaches & Hot Steps, a year later issuing Zydeco Excitement; after a lengthy hiatus from the studio, Delafose resurfaced in 1992 with Pere et Garcon Zydeco. 1993's Blues Stay Away from Me was his final album; failing health forced him to curtail his touring schedule soon after, and on September 17, 1994, Delafose died. Geno succeeded his father as bandleader.

Boozoo Chavis (born Wilson Anthony Chavis) was one of the pioneers of zydeco, the Cajun and blues hybrid originating in southwest Louisiana. Although his self-composed 1954 single, "Paper in My Shoes," was the first zydeco hit, Chavis was distrustful of the music industry and refused to perform publicly or record again until 1984. In an interview featured in the 1990 book, The New Folk Music, Chavis explained, "I got gypped out of my record. I get frustrated, sometimes. I love to play, but, when I get to thinking about 1955... They stole my record. They said that it only sold 150,000 copies. But, my cousin, who used to live in Boston, checked it out. It sold over a million copies. I was supposed to have a gold record." After leaving the music business, Chavis devoted his attention to raising champion racehorses in Shrevesport and Lafayette, LA and TX. Chavis waited until 1984 before returning to music. Signing a five-year contract with the Maison de Soul label, he recorded four albums -- Louisiana Zydico Music, Boozoo Zydeco!, Zydeco Homebrew, and Zydeco Trail Ride. Chavis' 1997 album, Hey, Do Right, was produced by Terry Adams, keyboardist for NRBQ, who paid tribute to Chavis in their 1989 song, "Boozoo, That's Who."

Chavis' performances, with his band, the Majic Sounds, included a much-heralded appearance at the Newport Folk Festival and the New Orleans Jazz and Heritage Festival. The New York Times wrote, "(Chavis is) chaos on two feet. A little bullet of a man, he runs around onstage, shouting and yelling....(his) music can achieve a trancelike intensity". In a review of Chavis' performance at the Southwest Louisiana Zydeco Music Festival, Paul Scott wrote, "There are a lot of Boozoo prototypes coming out. They may be smoother than Boozoo but they try to get his hard accordion; that rough, raw, style; and his sore throat type of singing. And with that single-note and triple-note accordion, he's doing a lot to bring a return to basic zydeco."

The son of tenant farmers, Chavis acquired his nickname as a youngster. Chavis was raised by his mother, who cleaned houses and sold barbecue at horse races until raising enough money to buy a three acre tract of land where she and Chavis moved in 1944. Acquiring an accordion from his father and teaching himself to play, Chavis was soon playing at local barn dances and in the dance club opened by his mother, where he often sat in with Morris Chenier and his sons, Clifton and Cleveland. In 1994, Chavis appeared in Robert Mugge's video documentary, The Kingdom of Zydeco. He was inducted into the Zydeco Hall of Fame four years later. Continuing to release music into the new millennium, Chavis issued Johnnie Billy Goat in fall 2000. On May 5, 2001 Chavis died after suffering from complications related to a heart attack he'd had a month earlie

Chavis' performances, with his band, the Majic Sounds, included a much-heralded appearance at the Newport Folk Festival and the New Orleans Jazz and Heritage Festival. The New York Times wrote, "(Chavis is) chaos on two feet. A little bullet of a man, he runs around onstage, shouting and yelling....(his) music can achieve a trancelike intensity". In a review of Chavis' performance at the Southwest Louisiana Zydeco Music Festival, Paul Scott wrote, "There are a lot of Boozoo prototypes coming out. They may be smoother than Boozoo but they try to get his hard accordion; that rough, raw, style; and his sore throat type of singing. And with that single-note and triple-note accordion, he's doing a lot to bring a return to basic zydeco."

The son of tenant farmers, Chavis acquired his nickname as a youngster. Chavis was raised by his mother, who cleaned houses and sold barbecue at horse races until raising enough money to buy a three acre tract of land where she and Chavis moved in 1944. Acquiring an accordion from his father and teaching himself to play, Chavis was soon playing at local barn dances and in the dance club opened by his mother, where he often sat in with Morris Chenier and his sons, Clifton and Cleveland. In 1994, Chavis appeared in Robert Mugge's video documentary, The Kingdom of Zydeco. He was inducted into the Zydeco Hall of Fame four years later. Continuing to release music into the new millennium, Chavis issued Johnnie Billy Goat in fall 2000. On May 5, 2001 Chavis died after suffering from complications related to a heart attack he'd had a month earlie